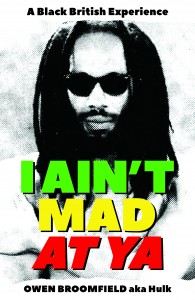

Hulk Interview for an Italian Magazine – ‘I Ain’t Mad At Ya’

Hulk Interview for Eventi Reggae – Italian Reggae Web Magazine

Danilo: Hey there and thanks for being here with us!

Owen: Danilo! Hello Danilo. Thank you for making the link with the man a big respect. Yes, I am truly honoured and blessed

D: Let’s start talking about when came out the idea of this book?

O: Yeah, I met with a couple of guys, Mike and Martin from Bristol, a company called Reggae Archives researching 70s Brum (Birmingham) reggae bands. They organised a band meeting were people were very enthusiastic about contributing recordings to an album released in 2015. I tried to retrieve some of our band’s material but I was unsuccessful. Martin or Mike suggested that I write a piece about my band and Birmingham’s music scene back in those days, so I wrote the album’s sleeve notes. After writing that piece for them I just didn’t stop writing. Shortly after, Mike told me that after reading my initial article his wife had cried. So I shared my, by then, manuscript with him which eventually led to a book.

D: Which was the purpose when you started to write it down?

O: I have great memories of my early years and music; together with a few unresolved matters that I wanted to get off my chest – this gave me the opportunity to set the record straight. I also felt that my humble musical achievements were note worthy and should be documented. As fragmented as the story is, the book depicts the truth about my early years and I also felt that that should my children become interested in their ancestry, they would have a starting point. I also hoped that my mates would enjoy the flashback and that people from England or abroad would appreciate hearing a first-hand account about how man and man reached Babylon.

D: In this book you’re describe the life of every afro-Caribbean young boy in Birmingham in the ’60s and ‘70s parallel to the musical scene that was developing at the time – How important and decisive was the music for that generation?

O: As I’ve indicated in the book, whilst life was not easy for black people in Aston, the older generation managed to create a vibrant music community here in Brum. Many of the early settlers were musicians that played Blue Beat, Rhythm and Blues and all the popular Motown hits in local parties, pubs and clubs; following this, the now legendary sound system began. For me music was always around – to put it simply; good food and reggae music was central to every Jamaican household.

For us born here in Babylon, it was a means by which we acquired knowledge of self, the teaching of the honourable Marcus Messiah Garvey, and our ancestry in Africa; the very things that many Jamaican parents don’t believe and if they do, they often refuse to discuss. So in the traditions of the African greats, our music acts like a time capsule capturing stories which download into the hearts, souls and minds of future generations. Music was in our homes, at church, and featured at just about any Caribbean event you attended. Reggae music speaks to the soul of the people in a way that no other medium can achieve. As a result everybody is touched by music, was in a group or a sound or, went to church which was another form of musical entertainment.

They say ghettos are the same all over the world. Reggae music is the voice of the sufferer and that can never change. So long as we have wickedness, poverty and crime, we will have the blessing of reggae music to soothe the soul of the sufferer.

The music of our parents is still relevant today, and our generation added the new British expression to the beat. That is the way, the truth and the life and I can categorically say that without a doubt, Jamaican people love their music.

D: Beyond the music, which were the “ambitions”, diffused between these young boys?

O: Everybody had dreams, and our families had great expectations of each of us. Like most immigrant families even today, the view generally held by our parents, was that our generation stood a far better chance of being successful in life because we were born in the UK. As young people back then we envisaged our whole lives in music.

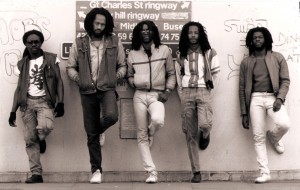

D: How was developing Reggae music? Which was the main local band at the time?

O: There were a few bands but I suppose, Steel Pulse was our reggae ambassador. Music from other renowned bands was not played in the dance hall, but rather forced on us through the radio stations. People were keen to hear a reggae beat on the radio, so anything remotely resembling bang-a-skeng-eh music would do the trick momentarily; so yeah, some commercial acts were appreciated. To be honest there was a wide variety of music making taking place all over Birmingham. Manz were churning out music both formerly e.g. Apache Indian making records from Whooly’s studio, and informally e.g. sound system dub plates. Only a few bands ever achieved chart success, but we never really saw those characters again. The night clubs were full of the London Lovers’ rock bands and the concert halls were overflowing with artists from Jamaica, including Burning Spear, Culture, Bob Marley, Dennis Brown etc. Outside of Jamaica this was the reggae capital of the world.

D: In every chapter you bring to life some of the musicians, giving a voice to these lost and hidden bands, encouraging the reader to discover them. Of these names, have you in particular you want to mention, because they played a particular part in your life?

O: There aren’t really any bands that played a particular part in my life, I guess you could say I’m a one band man. However, the most influential musicians around me were the McKoys and the brothers Johnson: Trevor, Fitzroy and drummer Boris. These brothers were simply amazing and truly gifted musicians and I was blessed to be there when they were young and took risks with the music.

Now if you asking about established acts, I love Bob Andy and Marcia Griffiths’, Young Gifted and Black which stands head and shoulders above all inspirational music to me. My mother used to play that Riddim regularly.

D: Coming from those years, how do you see the English’s society today? Has it change in good?

O: Personally, I don’t think society has changed a great deal since the 60’s and 70’s and if you look deeper into why the British wanted to leave the EU, the ‘selling point’ used was immigration. However, in some areas people have at times, learned to tolerate others a bit better. I don’t think that race or colour matters anymore to the youth involved in crime and furthermore, Jamaican culture has been totally assimilated. In the 70s our strong Rastafarian identity was everything; but now even though British youth culture is black culture, blacks as a whole are still on the bottom of the pile, the highest unemployed group and are over represented in the prisons and mental health system. Our communities are full of shop keepers from other cultures and very few blacks own businesses or have economic strength.

D: Have changed the problems of these new generations of Afro-Caribbean in the new millennium?

O: Nowadays, there are different groups which are affected in different ways. There are those born here in the UK, the first generation, who are now the elders in the community who still endeavour to pass on their cultural knowledge and upbringing. Then there are the second and third generations, e.g. my children and grandchildren, who have little or no affinity with the Caribbean foundation of their parents but instead pursue lives akin to our host nation.

D: Taking part in a reggae band, did you see changed Reggae Music today?

O: Reggae music is expressive which allows people put their own stamp on it. The notion of the charts didn’t exist for reggae musicians; the clamour for chart success is a totally British concept introduced into the Jamaican music business by sharks. For I and I the purist musician, it is far more important to make a tune which gets played in the dancehall and the hearts of people then subsequently exists in the reggae archives, than it is to have a number 1, one hit wonder.

D: What is the meaning that stands behind “I Ain’t Mad At Ya”?

O: Nuff things happen to a man in the Babylon system. I once heard a song with the lyrics: ‘I’ve gotta lot of pain in my heart, but I never let it reach my soul, I’ve been through a lot from the start, but I never knew how I stayed humble’ I’m not sure if it was a 2Pac track but those words stuck, inspired me and echoed my life. You see, there are many times when it would have been easier to get mad at situations, people, the disappointments, hurt and pain; but each time I rose above. So, there you have it, the meaning behind the name of the book.

D: Many thanks for your availability!

To order the book please visit: http://reggaearchiverecords.com/record-shop

Reggae Archive Records is a record label dealing in British Reggae from the 70's, 80's and 90's.

Reggae Archive Records is a record label dealing in British Reggae from the 70's, 80's and 90's.

Facebook

Facebook